Zakelj Diary

Home Page: http://bbhhs96.dyndns.org/~zakeljdiary/

Second Edition, 8/27/05

STARTING OVER

IN AMERICA

By Anton Zakelj, translated and edited

by John Zakelj

Translator's note: It's almost 10 years

since the Ameriška Domovina began publishing "Starting Over in

America." At that time, I translated six months from my father's diary as

a gift for my parent's 50th wedding anniversary. The reaction from

most readers was so positive that I continued translating more sections from my

father's diary and Jim Debevec was very gracious to continue publishing

everything I gave him. Since that initial publication, I have collected

additional photos and other information about our first six months in America.

Many people have mentioned that, of all the articles that my father and I have

published in the Domovina, these first six months in America were among the

most interesting. So, I present here a new, improved version. I hope that even

those of you who read the original version will find enough new information to

make this worth your while.

In Slovenia, my father was the manager

for a shoemakers' cooperative, and my mother was a seamstress and lacemaker. In

1943 and 1944, they were drafted at gunpoint to fight for the communists. They

escaped, and knowing they would face death or prison if they returned, they

left everything and became refugees. In 1946, they were married in a refugee

camp in Austria. After their marriage, they waited three more years in refugee

camps before they finally received permission to immigrate to America. They had

no idea what was waiting for them in a new country. When we arrived in America,

I was 16 months old, my mother was 35 years old and my father was 42.

In Wisconsin, a group

of Slovenian farmers agreed to be sponsors, to help refugees resettle in a new

country and start a new life. Our sponsors were John and Mary Brezic, who were

in their sixties and had themselves come to America from Slovenia in 1907

(John) and 1910 (Mary). They created their farm out of a logged over wilderness.

They had one adopted daughter, Helen, who was married when we arrived and was

living on a nearby farm with her husband. Mr. and Mrs. Brezic did not have any

other children, so it was a major change for them to now have a family with a

small child sharing their house. Their 80 acre farm barely supported them, but

they chose to share what little they had. This translation is dedicated to Mr.

and Mrs. Brezic and the good people of Willard, Wisconsin who made it possible

for many Slovenians to start a new life in America.

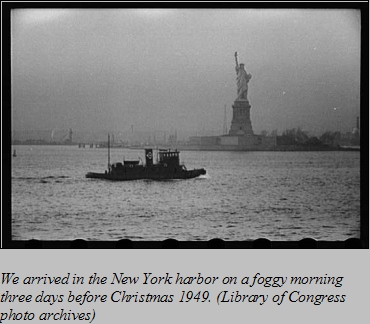

December 20, 1949

We've been on the U.S. Army Transport

Ship General Greeley for nine days and 3,520 miles. Today we made 402

miles. New York is 758 miles away. If all goes well, only two more days to go!

During the first week on the ship, we were so seasick we thought we would not

live to see America.

December 22, 1949

Many of the passengers got up at 3 or 4

o'clock in the morning. I waited till 5. I put on my best clothes for the first

time since we left land.

At 8 o'clock we saw, in the fog, the

first outlines of dry land: the New Jersey coast. There were many boats and

ships, and hundreds of gulls. I marveled at the unbroken line of cars along the

coast. They were all heading south. Was it a huge funeral procession?

At 9 o'clock we entered the New York

harbor area, and finally at 10 we saw the Statue of Liberty and the Manhattan

skyscrapers. My wife Cilka and son Johnny were with me at the ship's railing. I

had to keep a close eye on Johnny, since

he would wander off and be very friendly with everyone.

During the last few

days on the ship, we've been hungry and thirsty. We would have been so happy to

get some milk and bread, but they would not give us any. Today, in the New York

harbor, we saw the crew throwing large packages of food overboard.

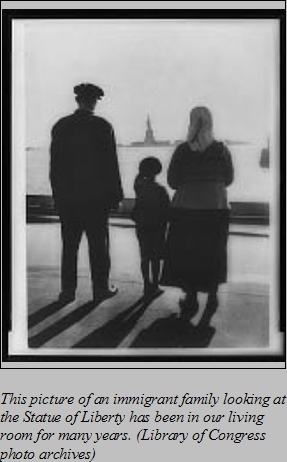

(Translator's note: Many years

later, I asked my mother how she felt when she saw the Statue of Liberty. She

said it was wonderful. It was a symbol of the freedom that we had been seeking

for so many years. But we were so tired, hungry and thirsty that it didn't

quite have the same feeling as you would expect. And the statue was also a

symbol of how far we had traveled and the fact that we would probably never be

able to go home again. That was very hard for her.)

At 10 o'clock a boat came to the ship

with a customs officer and a number of medical officials. There was no need for

X-rays, they could see right through our stomachs.

In the afternoon, we stepped on dry

land. We didn't stop at Ellis Island - it was just going through

decommissioning. They arranged us in alphabetical order and brought each

person's baggage.

(Translator's note: Our baggage

included two wooden crates which my father had made in the refugee camp. They

measured two feet high by two feet wide and three feet long, and were made from

boards which my father had obtained from a demolished barracks. Inside we had

all our belongings - basically items we had acquired during the past 5 years in

various refugee camps - blankets, clothes, pots and pans my father fashioned

out of the aluminum skin of a downed warplane, and a large quantity of lacework

that my mother had made in the refugee camps. Fifty years later, we still had

the crates and most of the things we had brought in them. The Western Reserve

Historical Society was very happy to accept them as a donation for a possible

future exhibit.)

I was worried I would have to pay customs

duties for the lacework. I talked to a priest about this, and he assured me

that everything would go smoothly. When the customs officer came to us, the

priest sent a pretty young woman to distract him. The customs inspection went

well.

There were some Jews who had larger crates

filled with valuable paintings by well-known artists. They had to open

everything up for the customs officers.

There were some Jews who had larger crates

filled with valuable paintings by well-known artists. They had to open

everything up for the customs officers.

We were greeted by women in grey

uniforms - I think they were the Daughters of the Revolution. They served us

coffee and donuts. I wished they had not taken the holes out of the donuts! If

I hadn't been so embarrassed, I would have gone back in line many times (maybe

I did). Later, we saw a man selling food in many languages - an apple, a piece

of bread and I think small cups of coffee - for a dollar. I bought food for all

three of us and spent as much as I had earned in three days of hard labor in

Austria. At these prices, the few dollars that we received from the National

Catholic Welfare Conference for the trip will be gone too soon.

It was already night when they put us

on busses and drove us through Manhattan to the train station. I looked out

from the bus and tried so hard to see the tops of the skyscrapers that I

developed quite an ache in my neck. I wondered how the driver could distinguish

the stop lights from all the other lights - everything was covered with red,

green and blue lights. (We were not used to Christmas lights.)

We had to wait about an hour at the

train station. I used this time to look for a loaf of bread for about ten

children - ours, Sršen's and Rihtar's. The grownups were hungry, too. But there

were no loaves of bread to be found anywhere - just sandwiches, so thin you

could see through them and expensive as saffron.

A gentleman walked around us a number

of times and looked us over. Finally he came to me and gave me a couple

dollars, and suggested I buy some candy for the children. I was grateful, but I

would have been much happier with a loaf of bread.

Around 11 p.m. we boarded the train. It

was a New York Central train, with large, shiny, new aluminum cars. On the

inside end of each car was a large mirror made of ground glass; stenciled on

the mirror was a map of the railroad's routes all across America. To us, this

train represented the greatness and comfort of America, just as Europe was

represented by the old, small wooden cars that brought us from Salzburg to

southern Italy.

In spite of our hunger, we soon fell

asleep and did not see the first part of our new homeland.

December 23, 1949

With other trains roaring past and many

red and green lights everywhere, I did not sleep well. Sršen's and Rihtar's

children woke before 6, our Johnny at 7:30. From 7 to 8 a.m., the train waited

in Buffalo. There were many factories everywhere. I wondered if they were

automobile factories since there were so many cars everywhere. I wondered about

all the wood houses. They seemed so poor, not like our stone or brick houses

back home. At home, only beggars lived in wood houses. Cars were everywhere,

but no people. I noticed some car cemeteries, too. Snow began to fall,

whitening everything.

In the morning, the train passed

through Cleveland. I'm not sure why this city interested me so much. Maybe

because I had read that this was the second largest Slovenian city in the

world? (Or did I sense that we would someday make Cleveland our home?)

As we traveled through Indiana, we gazed in awe

at the gigantic fields of corn, still unharvested. Next to the fields we saw

tiny houses here and there. We compared it to Croatia.

As we traveled through Indiana, we gazed in awe

at the gigantic fields of corn, still unharvested. Next to the fields we saw

tiny houses here and there. We compared it to Croatia.

Around noon we became hungry, but we

didn't have anything to eat. Sršen and I went to the dining car and asked about

lunch. All they had was tomato soup and sandwiches. An older black man served

us soup and then brought us sandwiches for the kids. Again, everything was so

expensive - soup was 50 cents and a sandwich a dollar.

Four gentlemen were sitting in the same

dining car. They became very loud during their meal; they were discussing labor

issues and not agreeing with each other. When the discussion  became

especially heated, one of them said, "Let's stop this and sing Silent

Night. It's almost Christmas." And they really did sing it - loudly and

clearly. This is much better than Europe, I thought.

became

especially heated, one of them said, "Let's stop this and sing Silent

Night. It's almost Christmas." And they really did sing it - loudly and

clearly. This is much better than Europe, I thought.

We reached Chicago at 5 p.m. There they

took us to a different train station, where we boarded an old Soo Line train.

After many short stops we reached Marshfield, Wisconsin at 4:30 the next

morning. During the trip our friend Sršen asked every passenger and the

conductor, in Croatian, "When will we get to the station marked on our

envelope?" (In Jugoslavia, we spoke Slovenian, but Serbo-Croatian was the

official language.) After every response, we knew less than we did before,

because none of us understood what anyone was saying.

In Marshfield, people were waiting for

us - Mr. Gosar, Mr. Brezic, Mr. Lamovec, Gosar's brother and others with 4

autos. Brezic recognized me immediately (from a picture I had sent him) and

offered me brandy, but I didn't want any. After an hour's drive, we arrived at

Frank Gosar's farm, where the Sršen and Rihtar families got off, while we

continued on to our new home. When we passed through the town of Loyal, I

particularly noticed the Christmas trees, hanging across the road and covered

with lights - it was as if they were celebrating our arrival.

These Slovenian-Americans talk a

strange mixture of English and Slovenian. For example, all containers are

called "boxa" - from small containers of matches to our baggage to the

biggest wagons and trucks - they're all "boxa".

At Brezic's house, "Lassie"

growled at Johnny when Johnny tried to pet him. Our new "mother"

warned Johnny very strictly, "Leave the dog alone - he's not used to

children." Then she said, "Since you've come two hours late, all the

food has grown cold and I don't have anything to serve you." She was

probably thinking we didn't deserve to be served, since we had probably stopped

at some bar. I remembered the words of the priest in New York who knew Mr. and Mrs.

Brezic: "You will need to be patient; John likes to drink, and  Mary can be pretty finicky."

Mary can be pretty finicky."

Lassie's barking reminded me of the

dreams I had in the refugee camp when we first heard that we had a sponsor in

America. When I learned that there are more cows than people in Wisconsin, I

imagined a mountainous region, since most cows in Slovenia graze in alpine

pastures. In my dreams, I saw a farm high on a mountain. Although the farm was

on a mountain, it was divided by a railroad track: even the buildings were

divided by the track - the house was on one side and the barn on another. When

the train stopped alongside the buildings to unload us, a "Lassie"

came to bark at us. Was it the same "Lassie" who growled at us this

morning?

By 7 a.m., we had warmed up and drank some

coffee, and then went to bed. We assured our new landlady that we were not

hungry, just sleepy. Oh, but were we hungry!

By 7 a.m., we had warmed up and drank some

coffee, and then went to bed. We assured our new landlady that we were not

hungry, just sleepy. Oh, but were we hungry!

When we got to our room, Johnny, who

had been sad for weeks, suddenly became so happy and excited that Cilka and I

just laughed at him and cried for joy. At last we all fell asleep and slept

till 11.

December 24, 1949

In Slovenia, a farmhouse is usually

bigger than the barn. Here, the reverse is true. The house seems small, and the

barn is large. I asked our host about that. He said, "You don't get

anything from a house; you earn your living from the barn."

The house is made of wood and laid out

in a "T" shape. The vertical part of the "T" has a porch on

both sides. The porch on one side is used for dirty boots and clothes, but the

porch on the other side does not seem used. The house seems of good

construction and arranged very practically on the inside. On the first floor is

the kitchen, the living room and one bedroom (where the Brezic's sleep); upstairs

is our bedroom and the water tank.

Outside, between the house and the

barn, is a tall windmill which pumps water from a deep well to the house and

barn. The outhouse is far to the back. During the winter, we use a bucket in

the basement, but that needs to be carried out every other day.

On the other side of the farmyard is a shed for 100 chickens and an old log cabin. John and Mary Brezic built the log cabin when they first arrived in 1914. For a number of years, they shared the cabin with two cows, some chickens and a pig. When they could afford it, they built their current house and barn. The log cabin is now used mostly for storage.

Today (the day before Christmas) was

supposed to be a day for fasting, but we had a good home style dinner. After

waiting many weeks, we finally had a satisfying meal.

In the afternoon I rode with John

Brezic and his son-in-law Frank Lamovec the 5 miles to Greenwood to buy spark

plugs for "our" Ford. We stopped at three bars (two Slovenian); at

one, Frank bought me an "egg nog", which I drank for the first time

(and probably the last time) in my life - it was good!

At the shoemaker's we bought rubber

boots for working in the barnyard and the snow (for $4.75). The shoemaker was

also a saddle maker.

John introduced me everywhere:

"This is my new man." He told me to only talk in English, and only

what was essential. He told everyone that I knew "dutch" (not

"deutsch").

At 4 p.m. we returned from Greenwood

pretty loaded. I can't believe that I really drank 3 shots of brandy, 1 glass

of wine and 1 warm Christmas drink. I talked with Slovenians, Croatians,

Americans and Germans, whomever my sponsor John introduced me to, all in their

own languages.

When we were alone, Frank said to me,

"You will not stay here, you are too smart."

After we returned home, I prepared

silage and hay for the animals, and then rode with Helen (Frank's wife) to my

friend Karl Erznoznik's. Karl and his family are living in a farmer's chicken

coop. We were all happy to see each other again after four months. (Karl and

his family had been in the same refugee camp with us.) His two year old

daughter Jolanda no longer recognized me. They are very satisfied - or so they

said. John invited Karl and his family to  dinner for tomorrow noon.

dinner for tomorrow noon.

At home a good supper waited for us,

then a rosary, and then opening of Christmas gifts. All the Lamovecs came. We

got presents, too! A toy car for Johnny, stockings and a scarf for Cilka, and a

checkered shirt and warm gloves for me. The others each got 5 or more packages

of practical items or toys.

Our sponsors proposed that we call them

"father" and

"mother", but we politely refused, because our own parents are still

alive (and because we didn't know if they deserved such respectful titles.) We

promised that we would call them "Uncle" and "Aunt." I feel

badly that I didn't express our sincere gratitude for sponsoring us and making

it possible for us to come to America when they didn't even know us.

At 11 p.m., Cilka and Mary rode with

the Lamovecs to midnight Mass. John, Johnny and I went to bed.

That night, John said we didn't owe him

anything. He had not had any expenses because of us; he had not even had to

sign the "affidavit" himself. If things don't work out, he said we

could go elsewhere, but he hoped we would stay with them. In the winter, he

couldn't pay us anything, because there wasn't much work; come summer, he would

pay me $50 a month. But later, he said that he thought a person should work for

his sponsor for a year without pay, since a sponsor had to buy additional

equipment or plant more fields to provide work for a new person. I was in

complete agreement with this idea, since I had expected that I would work on a

farm without pay for a year; however, I had also expected that, since we had

nothing, our sponsors would cover at least minor medical care. I noticed that

the "Farmer's Weekly" also said that every farmer who accepts a D.P.

(displaced person) could expect that person to work free for a year.

Weeks later, "Aunt" Mary told

me she had not agreed when John promised Father Odilo that we could come. This

was not right, since she was half owner of the farm. She did not want to be a

sponsor because she was worried I would drink and I would encourage John to

drink when he already drank too much. That's why she watched me closely those

first few days. Unfortunately, on my first day with them, I gave her cause to

worry.

December 25, 1949 - Sunday and

Christmas

"Uncle" woke me at 6 to feed

the livestock. Then we had breakfast - blood sausage, three pieces of bread and

more.

At 8:45 we rode with Uncle to Mass in

Willard. I was surprised by the Slovenian singing in the small, but beautiful

church. After Mass, we exchanged Christmas greetings and talked with people in

front of the church. Then John went to the social hall and bought three cases

of beer (!)

At home I cleaned out the cow manure in

the stable, then at noon the Lamovec and Erznoznik families arrived. After a plentiful

and excellent dinner, they talked and drank beer in the living room till 4.

Then Gosar, Sršen and others came. In the evening, I again helped feed the

livestock and, for the first time ever, milked cows. At seven we had a good

supper, and at 9 we went to bed. John advised me to work in the woods in the

winter and with him in the summer. He said someday I could take over his farm.

December 26, 1949

I got up at 5:45 and was in the stable at 6 to

feed and milk the cows. There were 16 cows, but we only milked 10. We used a

Laval electric milker, but we always had to finish milking each cow by hand. I

always washed the udders first with water and Lysol, then I attached the milker

until it was done, moved it on to the next cow, and so on. The daily schedule

was always the same: get up at 5:45, in the stable at 6, breakfast at 7, then

clean the stable and other work; at noon, lunch, then work, back to the stable

to milk the cows again at 4. On Sundays, I would clean the stable after

returning from church.

I got up at 5:45 and was in the stable at 6 to

feed and milk the cows. There were 16 cows, but we only milked 10. We used a

Laval electric milker, but we always had to finish milking each cow by hand. I

always washed the udders first with water and Lysol, then I attached the milker

until it was done, moved it on to the next cow, and so on. The daily schedule

was always the same: get up at 5:45, in the stable at 6, breakfast at 7, then

clean the stable and other work; at noon, lunch, then work, back to the stable

to milk the cows again at 4. On Sundays, I would clean the stable after

returning from church.

A few words about the barn: It's about

150 feet from the house, of very solid construction and quite large. The floor

is cement. Each cow is locked in its stall by a harness made of metal pipes.

The harness is flexible to allow the animal to turn, stand or lie down. Next to

each harness is a watering device: drinking water comes out whenever the cow

presses on the latch.

We use sawdust for bedding. Back home,

people had to haul their logs to the sawmill; here, they bring the saw to the

logs. Whoever needs boards brings their logs into a nearby open area; a person

comes with a tractor-driven circular saw and cuts the logs into boards. That

sawdust is then used for animal bedding.

The barn has a hand-powered system to

move manure outside: a small wagon hangs from a track mounted in the ceiling. I

use a chain to lower the wagon, shovel in the manure, then raise the wagon back

up. Then I pull it on its track out to the manure pile.

Next to the barn is a tall silo that

reaches high above the barn roof. Tall silos are a landmark all across

Wisconsin and rural America. Although they are built of various materials,

including wood, bricks and cement, they all have shiny aluminum cupolas that

reflect sunbeams many miles away. You can tell how large a farm is by the

number of silos. Some have as many as five silos. The Brezic farm has one silo.

The fodder inside our silo is mostly

chopped corn with cobs. The fodder can be thrown through a hole directly into

the stable.

Today, John and I went to church again

and visited with Father Odilo after Mass. I thanked him for helping us come to

America. He told me to work hard and be patient so that, in some years, I could

take over the farm.

At noon, it was just us for lunch and

Lamovec's children - 8-year old Judy and 4- year old Jerry. In the afternoon I

was free for the first time so I could read the newspaper. Cilka wrote to her

mother. The weather outside was beautiful.

December 27, 1949

John advised me to buy an old car from

Stamcar, who was hoping to sell it for $150. He said I had to have a car

"anyhow", if I wanted to stay here. But where could I get the money

for a car? John didn't want to loan it to me. Could we sell that much lace?

December 28, 1949

At 9 a.m. John and I went to

Marshfield, where he bought me overalls ($3.39), a shirt and hat ($1.19).

Marshfield is a beautiful town with many cars and one-story houses. We returned

home at noon. Cilka got a letter from her sister Manica. (We had sent the address

to our families earlier.)

All the people of Willard are extremely

friendly. Everybody asks me, in Slovenian-American, "Kako lajkaš novo

kontro?" (How do you like your new country?) If they see anyone walking,

they invite him to come sit and talk, and then they invite him to a saloon and

buy him a beer. When people asked me how I liked my new country, I usually

replied, "It's nice, but I am not yet here long enough to have an

opinion."

December 29, 1949

John drove to Willard to get feed for

the livestock and to take us to see Father Odilo, but he wasn't in. I received

my first letter from my sister Julka and my mother in Slovenia. They wrote on

December 15. In the evening, Cilka and I showed our sponsors her lacework, but

they didn't show any interest. Of course, cows and lace do not go well

together.

Translator's note: At this point, I

think it's worthwhile to interrupt my father's diary to learn more about the

history of Willard and its people. John and Mary Brezic were among the first

farmers in the area and very much a part of Willard's history. The following is

taken from "Spominska Zgodovina - Historical Memories", a collection

of writings and photographs assembled for Willard's 75th anniversary in 1982.

The following first two paragraphs were written by James M. Cesnik. The next

paragraphs were written by Rev. John Novak and translated by Josephine Trunkel.

The Willard area is - and has been

since the 20th century was in its teen-age years - the largest farming

community of Slovenian-Americans in the United States.

(In 1908,) the area around Willard was

a pocket of raw wilderness. It required the most arduous, bone-wearying toil to

convert it to farmland. It had been cut over by the N.C. Foster Lumber Co. for

its stands of virgin pine and white oak, but was still covered by the stumps

and substantial stands of maple, basswood, birch, ironwood and more. It was

accessible only by foot, horseback, or horse-drawn vehicle across rudimentary

trails or - the best access - via N. C. Foster's Fairchild and Northeastern

Railway.

The first settlers paid $4 to $20 per

acre, which was rather high considering the additional expenses involved before

this land could produce. The brush had to be cut and the roots and stumps dug

out, or pulled with horses and sometimes the large and more stubborn roots were

blasted with dynamite. Then they had to be hand sawed, piled to dry, and

burned.

Not only was this work slow, tedious

and difficult, it was also expensive. Many of these farmers said they would not

go through this work and suffering again, even if the land had been given to

them for free.

Most of the farmers came here with

enough money to pay for the land, but the two years or more before an income

began to return from it were very difficult for them. Besides the cost of

clearing the land, their families had to be fed and clothed. A few had

relatives from whom they could borrow, but most of them had to borrow from

banks and pay a high interest rate.

However, when the fields were cleared

and planted, the soil was very productive. The corn and grain grew tall and

yielded well. The grass in the hayfields and pastures was thick and produced

ideal feed for milk cows, growing calves and work horses.

Slovenian families now (in 1922) number

110, the average owning 40 - 80 acres of land. They are settled in a five mile

radius of Willard. Most of them now have large roomy houses and barns, though

many had started with one room log cabins.

(In addition, the Willard memories book

has the following about John and Mary Brezic:)

John Brezic was born in Austria in 1884

and came to America in 1907, at the age of 23. His wife Mary Marinsek was born

in Austria in 1891 (at that time, all of Slovenia was in Austria). Mary came to

America in 1910, when she was 19. John's first stop was at Meadowlands,

Pennsylvania where he worked in the coal mines. Mary started in Washington,

Pennsylvania, doing housekeeping. From there she went to Milwaukee. In 1912,

John came to Milwaukee and later they were married there.

In 1914 they purchased their forested

farm five miles northeast of Willard. They did their trading and attended

church in Willard, although Greenwood (located to the east) was a half mile

closer.

The farm was woods, brush and stones,

so it took many years to develop, but through hard work and much sweat it

became a modern farm. After purchasing their first few cows, they carried their

milk to the Gemeke corner which was about a half mile. This chore lasted about

a year, then they bought a horse.

The Brezics bought their first Model T

Ford in 1922. Their adopted daughter Helen came into their life in 1923 at the

age of 14 months. She was met at the railroad depot in Owen, Wisconsin with

horse and buggy. They often walked to church which was five miles away.

(And now back to the diary.)

December 30, 1949

We took a saw to Frank and a letter for

my father to the post office. Stamps were 40 cents - they wouldn't take the

international postal coupons I had bought in Austria. Mrs. Oman gave me three

old coats. In the evening we showed some lace to Helen. She marveled at its

beauty and gratefully accepted three pieces as a gift.

December 31, 1949

In the morning, I cleaned the cows,

then the stable. In the evening, we went to confession in Willard. At night it

rained. At 11 p.m. we went to midnight Mass for New Year's and communion.

During this past year, our deepest wishes have come true: we found a new homeland and we became members of a family where we can live without fear of persecution, torture or forceful death. We didn't come here to get rich but to find work to take care of ourselves and to be nobody's burden.

I'm worried about the relationship between our

sponsors. They sometimes do not get along well with each other.

I'm worried about the relationship between our

sponsors. They sometimes do not get along well with each other.

Could I do something to bring them

closer, or am I causing some of their problems? May God give me the grace to

know what to do!

January 1, 1950

A new year began today - hopefully the

beginning of a new life in a new country.

I woke before 6 as usual and went to

the stable. Cilka went to Mass at 11. I tried to sleep, but Johnny cried so

much that neither I nor Mary were able to comfort him. It was warm outside.

In the afternoon, I tried to sleep

again, without success. I felt sick and didn't eat supper.

In the evening, I explained to our

sponsors our predicament during the war. Cilka and I were opposed to communism,

but they drafted us at gunpoint. After we escaped, the communists considered us

to be deserters. When they gained control of the country, we had no choice but

to leave.

It was 10:30 when I finished our story.

I started feeling better, but John fell asleep and Cilka was angry.

According to the Holy Family Parish

annual report for 1949 there are 37 refugees in the Willard area:

1. Dusan Surman, sponsored by Mr. Anton Debevec, Sr.

2. Frank Brodar, sponsored by Mr.Anton Debevec, Jr.

3. Anton Kocjan, sponsored by Mr. Frank Perovsek

4. Alex Metlikovic, sponsored by Mr. Rev. Bernard Ambrozic

5. William Kuntera, sponsored by Mr. Alphonse Volovsek

6. & 7. Jakob and Martina Boznik, sponsored by Mr. Frank Volovsek, Sr.

8, 9 & 10. Karl, Marija and Jolanda Erznoznik, sponsored by Mr. Frank Volovsek, Sr.

11. Anton Asl, sponsored by Mrs. Mary Snedic

12, 13 & 14. Ivan, Branimira and Marija Berlec, sponsored by Mr. Ivan Ruzich

15, 16 & 17. Anton, Cecilija and Janez Zakelj, sponsored by Mr. John Brezic

18, 19, 20, 21 and 22. Miha, Katarina, Anton, Marijanca and Katarina Srsen, sponsored by Mr. Frank Artac

23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 and 31. Franc, Kristina, Franc, Milan, Janez, Miha, Marija, Pavla and Marija Rihtar, sponsored by Mr. John Kutzler

32. Janez Mrzlikar, sponsored by Rev. John Novak

33 and 34. Marija and Joze Androjna, sponsored by Mrs. Justina Volarich

35, 36 and 37. Marija, Stanka and

France Brecelj, sponsored by Mr. Anton Debevec, Sr.

January 2, 1950

The snow disappeared and in the evening it

started to rain. John and I worked on the water tank.

The snow disappeared and in the evening it

started to rain. John and I worked on the water tank.

John went to cook brandy from dry plums

and sugar, which he had bought in Marshfield on Dec. 28. John knew how to make

his brandy so it would look just like the commercial kind. He roasted powdered

sugar in a skillet until it became golden brown; then he shook that into the

bottles to make the brandy look just right.

January 3, 1950

John wanted to buy me Stamcar's 17 year

old car for $150, but I wasn't able to promise repayment and "Aunt

Mary" was against it: "You can buy an old car anytime you want,"

she said.

Eight cm. of snow fell today.

January 4, 1950

In the morning I froze part of my left

ear when I was hauling manure outside. There was a strong, cutting wind. In the

afternoon, we went to Karl's and to the post office.

In the post office I wondered about the

pictures of black men on the wall, with the large word WANTED under each

picture. What had they done to be so desired?

There are no black people in Willard.

All of us new arrivals refer to Africans as black people. The local people

laugh at us when we say that. The locals refer to them as coloreds or niggers.

There is one Indian family in Willard.

They live in a wooden hut outside of town. I've been told  that about half of the family died of

tuberculosis some years ago. They have a son who is a priest who is also sick. Farmers

hire other members of the family at harvest time. I have heard that they work

for beer, but people are not allowed to give alcohol to Indians.

that about half of the family died of

tuberculosis some years ago. They have a son who is a priest who is also sick. Farmers

hire other members of the family at harvest time. I have heard that they work

for beer, but people are not allowed to give alcohol to Indians.

January 5, 1950

It was -20F in the morning, 10 above in

the afternoon. In the evening I wrote to Mire, Cene, Vinko, and Frank in Canada

and to Paul in New York.

January 6, 1950

Today is the feast of the Three Holy

Kings, but there is no holiday on the farm. The temperature is again -20F in

the morning and 10F in the afternoon, 0F in the evening. I wrote to Jernej

Zupan and Jernej Kopac. All together I finished 7 letters.

January 8, 1950

Johnny has a cold and probably getting

a new tooth again. At 8:30 I went to Mass, then cleaned the stable. Mr.

Podobnik, who was in Goricia as an American soldier, came to fix the well. He

told me how he was arrested in Jugoslavia when he crossed the border.

Mr. Zagozen, the auto dealer from

Greenwood came offering Stamcar's car for $125. John thinks I should buy it. It

has only 24,000 miles on it, since no one used it after their father died. Our

Model A Ford truck has 72,000 miles - it's the tallest and the dirtiest vehicle

in the line in front of the church, but John won't let anyone wash it. Today,

"Aunt" Mary is not opposed to my buying the car either, but I don't

have any money and I don't know when I'll earn any. John already told me that

he can't pay me anything now when there isn't any work, but he'll give me $50 a

month in the summer.

Karl invited me to his place for

dinner. John turned down his request to borrow the brandy cooker. Aunt won't

allow it.

In the morning it was +6F, then +45F

and windy.

January 9, 1950

In the afternoon, Karl's wife Mici and

their daughter Jolanda visited us and invited us to come visit on Sunday. The

post office sent me a letter and 20 cents, since I had paid them too much on

Jan. 7 (they had finally accepted my international postal coupons). I helped

John balance his checkbook. The weather was warm.

In the evening, John, Frank (his

son-in-law), Mary and I went to Loyal to watch the film "Lion".

January 10, 1950

A snowstorm today. We were unable to go into the woods to get firewood for the church.

Mr. Zagozen came again to sell

Stamcar's car. In the afternoon, John and I went to Greenwood to fix the Ford.

I sold 6 pieces of lace for $14.50, which means we made 10 cents an hour for

the labor and nothing for the materials. I promised to buy the car if I could

sell enough lace. Mrs. Zagozen and another woman agreed to come look at our

lacework.

January 12, 1950

At 9 a.m. John and I went to the

location of a future resort, where they were cutting firewood for the church.

About 20 men came, all with their own cars. They cut the trees with power saws

and tractor-driven circular saws. At noon I chipped a tooth eating dried meat.

January 14, 1950

Snowdrifts blocked the roads and made

them impassable. The mail didn't come. Frank was going to come slaughter a cow,

but he didn't make it either.

January 15, 1950, Sunday

No one went to Mass today. It's 5 miles

to Willard in one direction and 5 miles to Greenwood in the other direction -

too far in this kind of weather. John and I fixed the tracks that help run the

manure wagon out from the stable.

Earlier, I wrote to Karl, telling him

we would come visit today, but now we can't. Even so, later in the day, I rode

with John to Greenwood to see Mr. Ford for help with the income tax forms. Mr.

Ford showed us his ten-year project - a miniature railroad with 5 - 7 tracks and

as many trains - all electric.

January 16, 1950

Johnny is getting his second eyetooth.

January 17, 1950

My father (back in Slovenia) is 71

years old today. We had chicken and other good food today - I wonder what he

had? In his first letter to me in America, he wrote that he would be very

grateful for some flour, if we have any extra. Unfortunately, I am not able to

help him.

January 19, 1950

I spent all morning cleaning the

stable. I felt tired, angry and unappreciated.

In the afternoon I split enough wood to

heat the house for two days, like I did every day. It was not good firewood

(aspen and birch), so we needed a lot for our four stoves (in the kitchen, the

living room, the basement and chicken coop).

Helen brought Mici to visit.

January 20, 1950

We received our "Identification

Cards." In the afternoon we visited Father Odilo. He advised me to stay as

a hired man at Brezic's, so I could someday take over the farm. Father Odilo

said the country is heading towards another Depression and terrible

unemployment. At the post office, I exchanged 4 English, 10 Austrian, and 13

American postal coupons for $1.35 and, later, an additional 10 cents.

January 21, 1950

In the morning I washed the cows.

Again, I felt tired and dirty. In the afternoon I made a new part for the

horse-drawn wagon since the old one was broken. I also worked on new handles

for the ax, the pick and other tools. John doesn't have woodworking tools and

isn't interested in woodworking.

January 22, 1950, Sunday

At 9 a.m. I went to Mass, then John and

Mary went at 10:30. After Mass I went to visit Karl. His sponsors let him live

in an empty chicken coop. They let him clean it and paint it. They  give him a quart of milk a day for helping with

the livestock feeding and milking. This is hardly enough to support his family

of three. We stayed for dinner (soup, potatoes, fried chicken, lettuce, apples

and pastry.) At 1, Mr. Rihtar and Mr. Sršen also came to visit. Karl proposed

that we all go work in the cement factory, or highway work, or construction.

give him a quart of milk a day for helping with

the livestock feeding and milking. This is hardly enough to support his family

of three. We stayed for dinner (soup, potatoes, fried chicken, lettuce, apples

and pastry.) At 1, Mr. Rihtar and Mr. Sršen also came to visit. Karl proposed

that we all go work in the cement factory, or highway work, or construction.

I will stay at Brezic's, even though I

know I won't earn much: I'm interested in farming and I owe my sponsors thanks

for helping my immigration. Karl hopes he will earn 80 - 90 cents an hour and

work 10 hours a day 9 months a year. The cement factory would provide housing,

too. He doesn't want to stay at his sponsor's because he doesn't like working

in the barn. Rihtar hopes he'll start building houses, and he'll need workers.

Mici showed us many clothes that good

people had given her for free. Sršen said people actually bring him too much

meat. At 4 p.m. John and Frank came to get us; after 5 hours of visiting it was

time to go.

January 23, 1950

The temperature was about +25F. Frank

Lamovec came to slaughter a cow this morning. In the afternoon, John took the

meat to the locker in Greenwood. They threw the hide in the snow for the foxes

and gave most of the fat to the cats. At Cilka's urging, they saved at least a

little of the fat to make soap. In the evening we cut up part of the backbone

for meals at home.

John promised he would pay me something

for my work on the farm, after I told him about my conversation with Karl and

Rihtar.

January 24, 1950

A snowstorm today. In the morning, John

and I tried to get to the barber in Greenwood, but we had to turn back after

half a kilometer. There were impassable drifts on the road.

January 25, 1950

Heavy snow. I cleaned the chicken coop.

January 27, 1950

In the afternoon in Greenwood, I dropped

off a letter at the post office for Milo Huber and went to the barber for my

first haircut in America. Haircuts cost 60 cents. In the Farmers' Store, they

promised to buy some lace.

January 28, 1950

In the afternoon John and I took the

horses into the woods to get firewood. The horses were strong, but they still

had to strain to pull the heavy wagon!

A man came in the evening and invited

me to go work with him in the woods. He would pay me $50 and necessities for

one month of hard labor. My wife could help in the kitchen to earn food for

herself and my son. How could I work in the woods in this kind of weather, with

the clothes I have ? I would freeze. (Later I learned that he had also invited

others - unsuccessfully, and that his workers are fed poorly and they have to

do additional saw work at the house after they return from the woods.)

When he left the room, I said to John,

"If I have to be a slave somewhere, I'd rather do it with you than with

someone I don't know and to whom I don't owe anything." But quietly to

myself, I wished God would give America another Lincoln.

January 29, 1950

Stormy. At 9:30 the others went to

church: John, Mary and Cilka. Johnny and I stayed home. Our old Model A is a

small truck; there's room in the cab for two, maybe three people at the most;

if anyone else comes along, they have to sit in the open wind in the back.

January 30, 1950

In the evening, John, Mary and Cilka

went to the wake for Mrs. Gosar's father. In the morning it was -38F: ideal for

splitting wood. You just let the axe fall onto the wood and the wood explodes,

because it's frozen. But I had to warm myself up inside the house first by

exercising so I would not freeze outside.

The silage was frozen up to a foot in

from the silo walls. It had to be crushed and spread in the stable to thaw out

and dry. Wet silage is dangerous for animals.

January 31, 1950

I went to the wake with John in the

evening from 8 to 11.

February 1, 1950

At 10 a.m. we went to the funeral for

Mrs. Gosar's father. John and I came back at 2. They had to use explosives to

dig the deeply frozen ground for the grave.

February 2, 1950

At 9 everyone except Cilka went to

church. In the afternoon I fixed the broken flooring for the horses.

February 3, 1950

Nice weather. For the first time,

"Aunt" Mary cooked "štruklje" at my request. They were very

good, with eggs and butter, but John didn't eat any. "I don't feel

good," he said.

During our first weeks on the farm,

Cilka often brought me a piece of bread when I was working in the barn or the

chicken coop. (I had set up a workshop in the chicken coop.) When

"Aunt" became convinced that I didn't drink, she said, "Tony,

since you don't drink, you can take milk, bread, oranges or apples from the

icebox whenever you want!" I gratefully took advantage of her offer -

whenever I was really hungry.

In the afternoon John and I went to

Greenwood. I sold $5.65 worth of lace at the Farmers' Store. When will I have

enough for a car?

February 4, 1950

At 11, I went to Neillsville for the

first time. At the courthouse they told me what I had to do to get my

"first citizenship paper". An old clerk named Frantz knew less than I

did. I think he filled out the wrong form. At the farmers' store I wasn't able

to sell a single piece of lace.

February 5, 1950

Nice weather. At 10:30 we went to

church, then from 1 to 3 at Stamcar's. They have 48 head of cattle, many pieces

of equipment and plenty of everything. They are the sponsors for Paula Rihtar,

but she isn't happy. Mrs. Štancar said "It isn't anything hard! Nothing

more than serving two boys; I don't know what's wrong." They served us

candy, beer, brandy, klobasa, bread, potica and coffee.

In the evening our sponsors went to

play cards and we went to bed. Our sponsors played cards at home sometimes, but

they would tell me, "You take care of your child, since you don't know how

to play cards." Johnny usually played by himself and I read. When I

interrupted his playing once, he said, "Don't bother me!" Where did

he learn to talk like that?

February 6, 1950

"Uncle" sold a three-week old

calf at 20 cents a pound for 97 pounds. Then we immediately got a new one. What

a fortunate birth! In the afternoon we hauled a wagonload of wood from the

woods.

February 7, 1950

February 7, 1950

In the morning we hauled in three wagonloads of wood, and in the afternoon we hauled the first of four large birch trees. Tiring work!

February 8, 1950

I fixed the manger for the horses.

Back in Slovenia, life must be harder

than it was in America during the Depression. "Aunt" Mary received a

letter from a relative, begging her for a bag of white flour. "Uncle"

did not agree, so Mary did not send the flour.

We have received other kinds of requests from Slovenia as well. "Uncle" received a letter from a relative, a young girl, who asked him to send her a pair of eyeglasses with golden frames. I advised him to ask her to send him

a prescription written by an

optometrist. He did, and the young lady responded, "No prescription is

necessary. The quality of the lenses is not important; the only important thing

is the golden frame." "Uncle" did not fill that request either.

February 9, 1950

Split wood.

February 10, 1950

I made a new floor by the door and new

"bridges" (across the manure ditch) for three cows. Another calf

born.

February 11, 1950

I cleaned the cows from 10 till 4. John

told me he had an argument with his wife.

February 12, 1950

At 8:15 Cilka and Johnny went to church. Mary

told me about her argument with John. She wants us to stay because we're a good

influence on her husband. He's been more peaceful and sober since we arrived.

At 8:15 Cilka and Johnny went to church. Mary

told me about her argument with John. She wants us to stay because we're a good

influence on her husband. He's been more peaceful and sober since we arrived.

Will we be able to live together? I am

having doubts about that. John never seems satisfied with my work. I can milk

the way he tells me today, but tomorrow he'll want it done differently.

Sometimes I'm feeling hopeless.

"Aunt" noticed this right away and asked John, "What was the

problem with you and Tony, why is he so sad?" John didn't answer.

February 13, 1950

I received a bill from the National

Catholic Welfare Conference for the train fare from New York to Marshfield -

$101.32. Where will I get that?

February 17, 1950

The first half of February was nice and

warm. around +20F in the morning and +40 to 50F in the afternoon.

February 18, 1950

At night cow number 9 gave birth to a

healthy calf. Since John's been cooking brandy, I have to feed and milk the

cows myself. John and Mary drove to Greenwood this morning and didn't return

till 1 because of the snowed in roads. "Aunt" Mary bought Johnny a

shirt, underwear and pants. For Cilka she bought cloth for a dress and apron.

February 19, 1950

+20F in the morning, +40F in the

afternoon. We all rode together to church. After church we went to Lamovec's

for dinner, which was like a wedding banquet. After dinner we went to Karl's

and brought him back with us. Everybody except me played cards; I read till

3:30. After a snack, Helen took Karl back home.

February 21, 1950

I cleaned the manger in the morning,

then split wood. It's Mardi Gras, so we had pastry and fancier bread this

morning. The Lamovec family came to visit in the evening. While the others

played "crazy" and pinochle, I played "old maid" with Judy

and Jerry (Lamovec's kids.) Although I was sleepy, I felt I had to keep the

children company till 11:30. Not a happy Mardi Gras!

February 22, 1950

Cilka woke me at 6 - John was already

milking, but he wasn't mad that I was late.

February 23, 1950

A light snow fell; colder.

February 24, 1950

-25F. Even though it was storming, I

went out and split wood. The colder it is, the better the wood splits.

February 25, 1950

-22F. I fixed a wheelbarrow and cleaned

the cows in the morning. In the afternoon I read till 2, then I split wood.

John is drinking less and is friendlier to his wife and to me, and is not

smoking.

February 26, 1950

I woke up at 5:20 and started milking at

5:30. John came later. He and Mary went to church at 8, then we went at 10.

Mary stayed with Helen, who is sick. Father Odilo Hajnšek said his farewells;

he's going to Lemont. We're very sad about that! He did a lot of good things

for us. Today, on the first Sunday in Lent, he called on the farmers to not let

the refugees suffer, to serve them the same food as they serve their own

families. Now we'll get a new priest, Father Augustin Svete, who probably will

not understand us.

Sršen and Rihtar came with their kids in the afternoon - they're the only people around here who get around on foot. They stayed till 4:30. Cilka treated them to gingerbread, which they ate a lot of.

In the evening, John drove to a card

party in the church hall, while I wrote and kept watch on a cow who was due to

calve. I watched till 10:30, but no calf.

February 27, 1950

John woke me at 2 in the morning, to

come help him in the barn. At 3, cow number 4 gave birth to a white calf. I

didn't go back to sleep. In the morning, I kept watch on number 5, who gave

birth at 11 with some difficulty. The calf barely stayed alive.

After a birth, we wash each cow with

Lysol and water. In the afternoon I split wood to stay awake.

February 28, 1950

This morning we took a calf to Volovšek's.

John received $25 for the 110 pound calf. At the same time, we bought a 200 lb.

pig.

The Volovšek farm has separate little

huts for each pig, spread out across the farmyard. In front of each hut is a

long wooden trough made from hollowed out tree trunks. The troughs have

corncobs and warm dishwater in them. Today, the pigs were running freely around

the farmyard. John chose a pig and tried to lasso him, but the pig took refuge

in his hut. John went into the hut after him, but the pig ran out. Somehow John

finally caught the pig and got him into a pigpen, which we then hoisted onto

the truck. The pig weighed about 200 pounds and cost $35.

On the way back, our truck slipped into

a ditch and barely stayed upright. Kranjc's tractor and four men pulled it out.

In spite of the strong wind and blowing

snow we came home safely. After we arrived back home, we had an argument about

cleaning the parking area.

In the evening there was a farewell for

Father Odilo, but I didn't go.

March 1, 1950

0F and it feels colder with the wind.

Aunt said she likes me and she hopes we

will stay. She is willing to do whatever she can to help us stay. She asked me

to just tell her what I would like to eat and she'll cook it for me. John is drinking

less now and is easier to get along with.

March 2, 1950

The mail didn't come today due to high

snowdrifts.

March 3, 1950

I used the woodworking tools to make a

new part for the wagon.

March 4, 1950

The weather has changed from the south;

it's become warmer.

March 5, 1950, Sunday

I woke at 3 a.m. and didn't go back to

sleep. At 5:30 I went to the barn and worked for two hours. John is criticizing

me more and more often when I am not at fault. I ate a little cornflakes for

breakfast and went back to the barn. At 8 the others drove to church while

Johnny and I stayed home. We went in the barn, where I cleaned and brought

silage from the silo. At 10 John drove me and Johnny to church.

In the afternoon Mrs. Stamcar and her

son Tony came to visit. Cilka, Johnny and I went to our room upstairs. It's

+36F outside and the snow is melting fast.

At 3:30 Stamcars left and Frank Lamovec

arrived. He called to us to come down, but I was writing a letter to my sister

Mici and brother Joseph in Slovenia.

Frank and I had an argument a few days

ago. He said that Bishop Rozman personally executed many thousands of people. I

was very angry to hear him repeating such lies and I corrected him. Bishop

Rozman was a hero to the people who fought against the communists in Slovenia.

Helen chided Frank and said "Tony knows what really happened - he was

there."

Someone has been spreading lies about

Bishop Rozman and all of us refugees - saying that we collaborated with the

Germans. Many Americans believe those lies. In the long winter evenings, I

often talk with John and Mary about all the suffering caused by the communists

and how we had all fought the Germans. John always listens without much

interest, and then he says, "And did you have to flee because you

supported Hitler?" It doesn't help when I explain to him that I was in

danger from both the Germans and the communists. In fact, the Germans held me

hostage and threatened to kill me.

When John accuses me of supporting

Hitler, Mary looks at him angrily and says "John, you're crazy!" She

has a brother who is a priest in Rome and who writes to her often. He provides

her with a better understanding of what happened during the war.

Later this evening, John tried to take

back the angry words he had said to me that morning. I kept quiet. I can see I  just can't work with him. I would take another

job immediately if I only could.

just can't work with him. I would take another

job immediately if I only could.

March 6, 1950

At every opportunity John tells me he

is sorry. He says we can live and work together nicely, since we think alike. I

only reply "Yes, in some areas."

March 7, 1950

Our sponsors had a very serious

argument at breakfast. Mary is angry that John offended me. She's threatening a

separation.

John promised I would be paid from now

on if we would stay. I told him that I still didn't know what we would do. If

we can get along, I'd like to stay, but never if we'll continue arguing.

"I'd rather starve than live in a constant dispute." I told him that

we would both have to be patient and let some things go quietly, including him,

not just Mary.

I wrote to Jernej Zupan in Cleveland

and sent him lace worth 58.70 shillings for books from Mohorjevo publishing. I

asked him to find a job for me.

John and I went to Willard in the

morning. In the afternoon we had a downpour and water in the barn. I cleaned

out the water and spread sawdust on the floor.

John is scrupulous about cleanliness in

the barn: there is always a pile of lime next to the door. Anyone who wants to

step into the stable area has to wipe his shoes in the lime first. "Lime

kills germs", John says. I often have to spread this pile of lime across

the entire length of the stable and then sweep it back into a pile.

March 8, 1950

John said he'd rather just leave now

than have another argument with Mary.

March 9, 1950

Milica Zonta wrote from Neelyville,

Missouri. She and Rafko are in the same situation we are: lots of work and no

pay.

John became sick yesterday. Mary and I

are milking the cows.

Today I split wood for four hours.

March 10, 1950

John has a stomach ache and the flu.

John advised me to write to Rev. Wolfe,

the pastor in Bangor regarding the bill for the train fare from New York to

Wisconsin. He gave me a check for $50 (to send in) and suggested I ask for a

delay or reduction on the remaining $51.32.

This Monday we started using two

milking machines to milk 13 cows. Milking takes about an hour. When we used one

miler, we milked fewer cows. When we've filled 5 big cans (about 200 liters),

I'm soaked with sweat, even with the help of the milking machines.

March 11, 1950

John went to see the doctor in

Greenwood. Dr. Olsen told him that he was sick because he's holding his anger

inside and not letting it out like he usually does.

Rihtar and Sršen went with John to get

letters brought by Milica from Austria. They are also working without pay at

their sponsor's farm.

John felt better after he came back

from the doctor. Now Mary is starting to feel sick.

March 12, 1950

Mary stayed in bed. Johnny is sick,

too. John and I went to church, but we got there late because we tried -

unsuccessfully - to help Helen get her car out of the snow on the way there.

Lamovec's came to dinner.

In the afternoon, Frank took me and Helen

to Greenwood. Helen went to ask the doctor about Mary, while Frank took me to

see a bar and bowling alley and drink beer. We returned home at 1:30, and then

Frank took me to the northwest across a hill to a Slovenian restaurant, which

was modern but in the middle of nowhere. They had an automatic record player

with 20 records.

People at the restaurant talked about an old man who died recently. He worked as a farmhand all his life. His master gave him his daily bread and a bed with the animals in the stable, but never a penny. People were upset about this and criticized the farmer. The farmer promised to buy the man a tombstone. Is the same destiny waiting for me?

At 3:30 we returned. From 3:30 to 7:30,

I worked in the barn as usual. Frank promised to teach me to operate a tractor.

He is becoming quite friendly.

March 13, 1950

"Aunt" Mary and Johnny are

healthy again.

Instead of a tractor, the Brezic's have

two strong horses. All winter they only went out a few times to haul wood or to

smooth the road. They were inside so much they grew very long hooves. John had

to set the hooves on a chopping block and cut them back with an axe.

One of the horses likes to kick and

bite. If anyone gets close to him without warning, he immediately kicks. Once I

was working at the other end of the barn when I heard a horse neighing at the

end by the doors. I looked and saw little Johnny next to the horse. I called

out to him and told him to stay completely still. I ran over, patted the horse

gently and pulled Johnny away. It's a mystery to me how a year and a half-old

boy could have opened the heavy barn door and come in by the horses.

March 14, 1950

Johnny cried out last night: "Mama,

no!" Helen drove to the doctor and asked about Cilka, who is now two and a

half months pregnant and is bleeding. The doctor said Cilka needed to go to the

hospital immediately. At 12:30 in the afternoon, Helen took her to Marshfield.

Helen came back at 9 in the evening. She said Cilka was operated on

immediately. Cilka feels better, but she's lost the baby.

Johnny cried out last night: "Mama,

no!" Helen drove to the doctor and asked about Cilka, who is now two and a

half months pregnant and is bleeding. The doctor said Cilka needed to go to the

hospital immediately. At 12:30 in the afternoon, Helen took her to Marshfield.

Helen came back at 9 in the evening. She said Cilka was operated on

immediately. Cilka feels better, but she's lost the baby.

It's been many years since I've cried

as much as I did today; my head hurts from the crying.

March 15, 1950

I slept poorly. John woke me at 5 and

told me I could stay in bed; he said he would feed and milk the cows. I woke at

6, heated some coffee and fried some eggs. At 7:30 John came to clean the sink

and I went to clean the stable. Mary came back from Lamovec's, where she had

stayed the night. Around 11, Helen drove me to Marshfield. Cilka is feeling

well and will come home tomorrow. Mary sent oranges for her, Helen bought her

chocolate, candy and a comb. We stayed in the hospital till 3 p.m.

It's only now, when Cilka's sick, that

I realize how much I love her. What would I do by myself? A slave on a farm

till I die! And our Johnny will be a slave, too. I will want to send him to

schools, so he won't have to suffer like I have, but I won't have the money to

pay for his schooling.

Helen, Frank, John and Mary all tried

to comfort me. They said Cilka was not in danger and would be home soon,

completely healthy. But I kept thinking about the worst things that could

happen. I went to the barn and cried.

March 16, 1950

Helen went to Marshfield in the morning

to get Cilka. She brought her home at 3:30 p.m. The bill for two days in the

hospital was $29.25, but they reduced that to $20.95. In addition, the

operation was $50, anesthesia $10 and John paid Helen $15 for transporting us;

therefore, $95.95 total, or two months of work on the farm.

March 18, 1950

Warm. I worked in the barn in the

morning. John and I went to church for confession in the afternoon.

March 19, 1950, Sunday

I got all my work done in the barn by

7:30, then went to church with John and Mary. More than 100 men received Holy

Communion, as members of the Holy Family Society.

After Mass, we had breakfast in the

church hall: coffee, potica, donuts, cookies, sausage, meat (both pork and

chicken) and more. Those who could afford it, paid; others who could not, ate

for free - just like in the early years of the Christians!

The women's society members brought

homemade potica and cakes to be sold for the society. If a piece didn't attract

a buyer, the woman who made it bought it herself to prevent embarrassment.

In the afternoon we had visitors:

Ludvik Artac and his parents, then Malci Jeras with two kids and Karl with his

family, then the Lamovec family and finally Sršen's. Sršen and Karl want to

find work elsewhere as soon as possible, preferably together. Sršen asked me to

help him answer an ad for work at a Shoe Service. He gave me 20 cents for

helping him, the first two dimes I earned in America.

March 21, 1950

It's the first day of spring, but it

snowed all day. Yesterday I moved 100 bushels of oats and 12 sacks of

fertilizer. Today I split wood. John is usually milking by himself. Since I

never seem to do things right as far as he's concerned, I try to not work with

him. I am becoming more ill-humored, quiet and withdrawn. This can't go on much

longer.

March 22, 1950

About 5 - 6 inches of wet new snow fell

today. In the morning, I went to Greenwood with John to buy leather, but the

shoemaker only had pieces of horse leather that were about 30 inches square. On

the way back, we saw Sršen, who said that Rihtar got a job in Cleveland as a

carpenter at $3 an hour. He will go to Cleveland this Saturday.

March 23, 1950

I wrote the Marshfield Clinic and asked

them to reduce the bill for Cilka's operation.

Lamovec brought 25 sacks of potatoes

from Stevens Point. They cost $10, or less than a penny a pound. Since the

potato harvest was plentiful last year, they are selling potatoes for animal

feed, with government support.

In the evening, Mrs. Rakovec visited with her

son Ciril and his wife and daughter. Ciril made a very positive impression on

me. Although we had not met before, he suggested that we each get a week's

vacation this summer: when one goes on vacation, the other takes care of his

chores. Ciril knows John well. He worked for him as a hired man for a few

months and understands that he's impossible to work with. If we were staying

here, I would become best friends with Ciril. But since I hope to move

elsewhere before too long, I kept quiet and went to bed at 9:30, while the

others talked till 11. (+60F)

In the evening, Mrs. Rakovec visited with her

son Ciril and his wife and daughter. Ciril made a very positive impression on

me. Although we had not met before, he suggested that we each get a week's

vacation this summer: when one goes on vacation, the other takes care of his

chores. Ciril knows John well. He worked for him as a hired man for a few

months and understands that he's impossible to work with. If we were staying

here, I would become best friends with Ciril. But since I hope to move

elsewhere before too long, I kept quiet and went to bed at 9:30, while the

others talked till 11. (+60F)

March 24, 1950

John went to Marshfield with Frank, but

they weren't able to get the right kind of leather there, either. I worked on

the bull's stall. It's a waste to have a bull for 16 cows; the bull and the two

horses eat more feed than 4 cows, and don't provide any benefit. It would be

cheaper if, instead of the bull, we used artificial insemination, and instead

of the horses, asked Frank to help with his tractor.

After three months in America, we have

nothing and are $200 in debt.

March 25, 1950

I cleaned the cows in the morning. The

Marshfield Clinic responded to my letter; the bill for Cilka has been reduced

from $85 to $60, but this must be paid immediately.

March 26, 1950, Sunday

At 10 o'clock, we went to church. On

the way to church, we got stuck in deep snow and mud. When I was pushing the

truck to get it unstuck, John stepped on the gas and sent mud flying all over

me. I had to go back and change clothes.

The roads here are hopeless, like

nowhere in Europe. They're just sand, pushed in from each side. When melting

snow soaks the sand, cars swim in mud up to their axles. When the ruts on the

nearby road get too deep, John sometimes goes out to level the road. He uses

his team of horses hitched to a kind of harrow made of six 8-foot long tree

trunks bound together with chains. Of course, this lasts only for a couple

cars.

After Mass, John took Karl back to his

home. Sršen and I decided to look for work in Marshfield, maybe in the shoe

factory.

In the afternoon and evening, I wrote

to my brother John and my mother in Slovenia, and to Jesenko's in Cleveland.

Outside, it was windy, rainy and muddy.

March 27, 1950

John woke me at 5 a.m. to help with the birth of

a calf which was already 10 days overdue.

John woke me at 5 a.m. to help with the birth of

a calf which was already 10 days overdue.

In the afternoon, I cleaned the area

around the well. The farm has a windmill which pumps water and sends it to the

kitchen and the stable. Large sheet metal water tanks are located all around

the farmstead.

Helen and Cilka worked on a quilt they

are making from 1,000 pieces of cloth. While they sewed, Mary talked about how

it was when they first bought their land around 1910. There were no roads

nearby. Mary and John bought 80 acres that had never been farmed - the big

pines had been logged off earlier, so when they got the land, it was mostly

brush and aspen. They built a log cabin, really more like a shed. Although

there were a number of other Slovenian families that also bought land in the

general area, there were no other houses nearby. After John and Mary bought

their first cow, the cow slept in the cabin with them.

Mary said life was alright in the

summers in those early years. But, during the winters, John would go work in

Chicago because they needed the income. She was alone all winter in that little

cabin. She didn't have horses or a car, so she had no way to travel anywhere.

On rare occasions, the neighbor came to visit; or even less often, John would

come visit from Chicago. He would take the train to Marshfield and walk from

there to the cabin, which was almost 20 miles away. There were no busses.

Mary said there was a stranger that

came to her cabin one winter's day. He was either lost or on a long trip. She

was very afraid of him, but she fed him supper and let him stay overnight. The

next day he moved on and she never heard from him again.

Over the years, John and Mary gradually

cleared more land for farming. They planted potatoes. Things got better and

better. They built a nicer house and converted the log cabin into a barn.

March 28, 1950

Sršen and Karl went to Marshfield to

look for work.

April 2, 1950, Palm Sunday

At 8 am, we all went to church. I rode

in the open back of the truck, freezing. At church they had palm branches, not

"butare" like we used to have in Slovenia.

Karl and Sršen will begin work in the

Marshfield shoe factory at the end of the month.

I wrote to Jakob Kopac in Chicago. He

is a distant relative who might be able to help me get a job.

April 5, 1950

Jernej Zupan sent me a check for $33

for the lace I had sent him; he writes that he will find work and housing for

me in Cleveland. I wrote back to him in the evening. I also wrote to my

brother-in-law, Mire, in Canada, asking him for money.

April 6, 1950

In the morning, John asked me "Did

you hear how sadly a deer cried last night?" I said, "No, I

didn't." We went out to the road to see what had happened. We found some

bloody spots only partly covered by sand and deer hair. We decided that a

hunter must have used his car lights to attract the deer. The deer paid for its

trust with its life.

In the afternoon, John and I burned

brush in the pasture. Even though there's water everywhere, the brush still

burns.

April 7, 1950, Good Friday

This afternoon we all went to church.

From 2 - 3 pm, we listened to the passion of Christ and prayed the Stations of

the Cross.

The weather was warm and beautiful.

April 9, 1950, Easter Sunday

I finished my work in the barn by 7:40.

At 8 a.m., we all went to church together. Cilka and I sat in the open back of

the truck; it was a cold five miles to Willard. When we returned, we ate the

blessed food. In the afternoon, the Lamovec family came for dinner - good and

plentiful! Then Helen took me to Sršen's. Sršen is going to Cleveland tomorrow

to look for work. I don't know what happened to the plans for work in

Marshfield.

April 10, 1950

It rained all day, and the snow on the

ground turned to ice. In the morning, John and I turned the hay, and then

cleaned the granary.

I think about how we used to celebrate

back home on the Monday after Easter and I feel sad. (Easter Sunday and Monday

were both celebrated as holidays in Slovenia.)

April 11, 1950

I finished my work in the barn by 9

a.m. John took oats to the mill. I was free and bored till 4 p.m. And yesterday

we had so much work.

April 12, 1950

John had often mentioned that we would

need to fix the horse's leather harness. It was never oiled and was broken. I

was worried how we would do that without the right tools. But we managed to fix

it with rivets. We also fixed the manure wagon.

April 13, 1950

Our sponsors had another argument this morning.

Mary was helping John in the barn when the argument started. She said she would

never come in the barn again. John was mad all day. Angry, he used a hammer to

smash three wheels on the manure wagon and the chain we use to lift the wagon.

Now it's all useless.

Our sponsors had another argument this morning.

Mary was helping John in the barn when the argument started. She said she would

never come in the barn again. John was mad all day. Angry, he used a hammer to

smash three wheels on the manure wagon and the chain we use to lift the wagon.

Now it's all useless.

In the evening, I wrote to the

university in Madison. They had advertised a free correspondence course in

veterinary science. I was excited about this and hoped I could help myself and

others with this knowledge.

April 14, 1950

I worked all day to make a wheelbarrow

to replace the manure wagon..

At 10 a.m., Frank came to slaughter the

pig. In two hours, the pig was beheaded and cleaned. The pig had grown almost

100 lbs. in 45 days, eating nothing but corn. He weighed almost 300 lbs.

It was a beautiful spring day.

April 15, 1950

In the morning, I took care of Johnny

while Cilka helped to cut up the pig. In the afternoon, I split wood till I got

too hot.

In the morning we ate blood sausage,

then pig roast for lunch and supper.

April 16, 1950

At 8:10 we all went to church. Johnny

stayed in the back with me and slept. After Mass, Malci Jeras took us to

Karl's. In the afternoon, we went with Karl to a 100 foot high observation

tower. From the top of the tower we could see for 20 miles all around. The

observer in the tower showed us his instruments, binoculars and map. By chance

I embarrassed the observer by noticing some smoke before he did. He determined

the location, called a nearby farm and learned that it was a grass fire.

April 17, 1950

Hot. My right eye hurts.

I told John that Americans don't

understand the value of manure: they let it dry out, or they let it run down to

the creek. I suggested that we build a manure pit behind the barn and cover it

with small logs. "Oh, that's not worth it," he replied. "That's

done by people who have no money for fertilizer. Besides, don't you see that

the cows don't eat the grass that grows on the manure?"

In the afternoon we went into the

woods. We were not able to cut up a large aspen. We tired ourselves out using a

dull saw and axe. If I had had a file, I would have tried to sharpen them, but

I didn't.